Singing in a choir

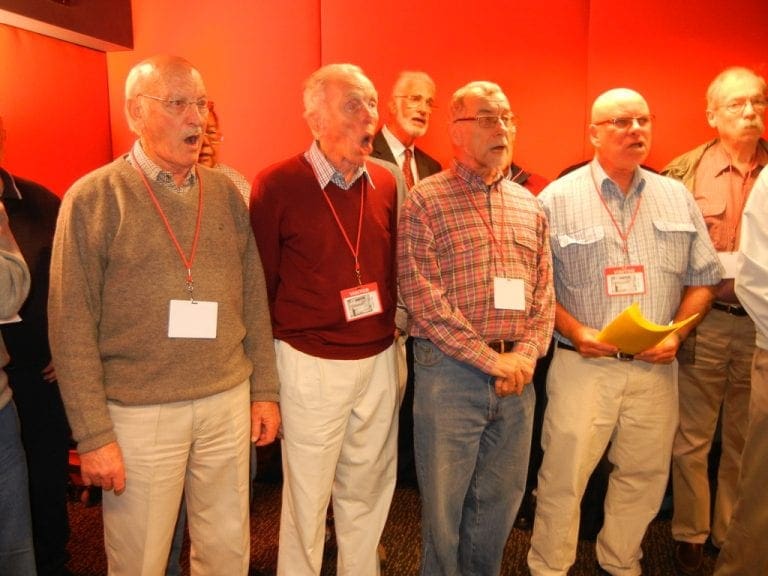

I am one of 13 Basses with the Sydney Male Choir. The choir has about 65 members. About equal numbers of Tenor 1, Tenor 2 and Basses and a few more of Baritones (which is of course the normal male voice range). In most pieces of music, each of the four parts has its own little tune to sing. Tenor 1 or Baritone usually get the melody that everyone will know. If the arranger has done a good job, the Basses and Tenor 2s will also have a memorable tune. We sing from memory – that is, without holding music. Although that does make leaning our part a little more difficult, we sing and sound much better without our heads stuck in the music; watching, listening and blending.

Below is a Youtube of Sydney Male Choir

I’ve been singing in choirs for about 11 years. Why? would be a good question. I actually find this an extremely rewarding leisure activity. It certainly used to be a lot more common for people to sing in choirs before TV took over their lives and persuaded them that you have to be an expert before you can sing. Almost everyone can sing. If you can whistle, you can sing. But why is singing with a choir so interesting. These reasons for me:

- A building process. Beginning with a piece of music that we don’t know and cannot sing and work individually and together to learn it and produce it in front of a paying audience. It usually takes about 6 weeks but can be much faster. That process is very satisfying.

- Learn to solo level. Each one and every one of the choir has had to learn the piece almost to the level of a soloist. However, having achieved that as a basic level, each and every person has to then work with everyone else to produce it.

- Listen and blend. Knowing our part very well, we each have to listen to what the other people in our part are doing, what the other parts are doing (for our entries), what the piano is doing (for the tempo and to keep in tune). Don’t stand out but provide the volume level needed for each phrase. Keep in tune and help everyone else stay in tune.

- Watch the conductor. Absolutely critical. Each time we sing a piece it is a unique performance. If does not matter how well you might know it, expect the conductor to vary the tempo, hold notes for different lengths. The conductor makes each performance of each piece what it is. The conductor has to take what is essentially a group of soloists (who are trying to work together) into a blended whole. Choirs that try to work without a conductor have a very poor chance of success.

- Work with others. None of us can do it by ourselves. Almost no part will have the melody for very long. All the other parts are usually singing in harmony with each other. We seldom sing the same words with the same tempo for all or even most of a piece.

- Memory. Having to learn each piece by heart is great for my memory and aged brain. I find that something begins to happen after a few sings through and after something like 15-20 times through the song gets into my head. After 50 times through, it becomes easy. The secret appears to be “don’t try too hard for accuracy on any one sing – it is the number of times through that counts”.

- Community. All of this gives a huge feeling of community. Of belonging and pulling one’s weight.

- Effort. All of the above indicates that there is a large effort by everyone in the choir. Hard yet enjoyable work.