I am the Museum of the Orangerie

I am a purpose built museum to hold Claude Monet’s crowning work, his waterlily series which fill two oval rooms on my ground floor. The series of eight huge canvases were painted in his garden at Giverny.

Like Beethoven going deaf, an almost blind Claude Monet drew his final works on a monumental scale. Even as he struggled with cataracts, he planned a series of 2 metre tall canvases of waterlilies to hang in special rooms at the Orangerie.

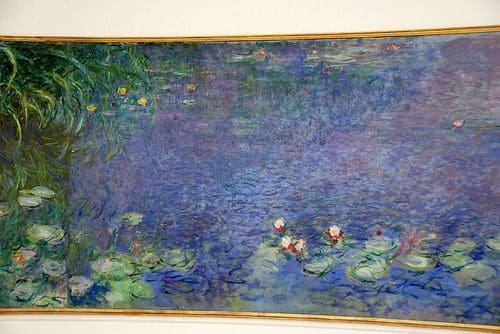

These eight huge curved panels immerse you in Monet’s world. You are looking at the pond in his garden at Giverny – waterlilies surrounded by the changing light reflected from the water – sky, clouds, trees, foliage, ripples all show on the surface of the water.

In the first room, four canvases show the pond at different times of the day: early morning with dark sombre colours, morning full of light, afternoon with clouds reflected and at sunset with a fiery sky. The morning canvas is clearest. The blue pond is framed by green banks with lilies dominant in the middle. In each canvas, the same lilies are in the same place – the centre of the pond. However, the light changes with the time of day.

The scale of the enterprise of the Orangerie/waterlily project should have been daunting for 74 year old Monet when he began it in 1914. He worked on it for 12 years until his death aged 86 in 1926. The ‘morning’ painting alone is made of four separate canvases sewn together and spanning 16.75 metres. Working at his home in Giverny, Monet built a special studio with skylights and wheeled easels to handle the huge canvases.

The real subject of these works is not the waterlilies. It is the play of reflected light from the surface of the pond. Monet would work on several canvases at once. He would move with the sun from one canvas to the next to show the reflected light for different times of the day.

The truly amazing thing is that there is not a waterlily flower or leaf painted anywhere. When you stand close, all you see are apparently tangled brush strokes, layers and different colours. Step back a few paces and the tangle becomes – waterlilies.

In the second room, the same lilies are still in the same pond. However, now Monet has added trees to give a frame and ripples for wind.

Monet excels in suggesting the drawing of light. He makes us understand the movement of the vibrations of heat, the movement of luminous waves; he also understands how to paint the sensation of strong wind. Madame Morisot said, “Before one of Monet’s pictures, I always know which way to incline my umbrella.”

Monet completed all eight painting before he died but did not live to see them installed in the Orangerie. In 1927, the year after his death the Orangerie rooms were completed and the canvases put in place, in specially built rooms that allowed natural light from above.

It did not end there. In the 1960s, it was decided to add a floor above the Monet waterlilies to house the very impressive Paul Guillaume collection. However, that cut the waterlilies off from the light and that was, after all, their inspiration and subject matter. In 2006, after a renovation that took six years and a few tens of millions of dollars, the Guillaume collection was moved underground and the waterlilies were again drenched in light.

The Guillaume collection is not to be sneezed at. The underground galleries hold selected works from the personal collection of Paris’ trend-spotting art dealer of the 1920s, Paul Guillaume.

The works shown are all beautiful.